Navigating a Whackadoodle World: Episode 65, The Power of Responsibility, or When your gut leads you wrong.

A Whackadoodle lesson featuring two memory techniques, a review on cognitive biases, and reminder about the power of response-ability, along with a confession about what tanked my acting career.

She had a psychology test the following day and was woefully unprepared. I repeated my review question for a third time, “What’s cognitive bias?”

“Shush,” she shook her head. “I’m thinking.” Eventually she came up with an answer, “Cognitive bias is the one where we tend to seek out and prefer information that supports our preexisting beliefs, and we tend to ignore any information that contradicts our beliefs.”

I made a sound like a game show buzzer, followed by, “That’s Confirmation Bias. Try again.”

“Arggh,” she slammed her hands down on the table before her. “Why do they all have to sound so much a like?”

I shook my head, “Your problem is that you’re trying to memorize all thirty-seven of them in one sitting.”

“I know. I know. I should have done the card thing.”

She was referring to a technique that I had taught her years ago which moves your short-term memory input into your long-term memory storage. Repetition over time is the key. It goes like this: (If you’re not interested in the technique, feel free to skip ahead.)

Memory Technique

Day One: Write out any information that you want to retain long-term on note cards and review the cards three times that day. Try to make one of those times be just before you go to sleep. Somehow, sleeping on it does seem to help the memory.

Okay, you don’t have to write it down, you can just do the recall. However, the note cards help with the recall, especially if you are trying to recall a long list of items. For example, if you are just trying to remember someone’s name, note cards may not be necessary. However, if you are trying to recall a list of 37 biases, note cards kind of become essential.

Also, if you are trying to remember a long list of items, you might want to start day one with just three of the items, and gradually add three more cards each day until you have your full list.

Day Two: Review your list from the day before, adding any new items should you wish. Items that you can recall easily, go into a pile called, ‘I know it’. Items that you cannot recall easily go into a pile called, ‘I need to review it more.’

The ‘I know it’ pile should be reviewed once a day for a week.

The “I need to review it more” pile should be reviewed at least three times a day.

Whenever you can recall one of the ‘I need to review it more’ items easily, you can move it into the ‘I know it’ pile, and if you get stuck on something in the ‘I know it’ pile, you can move it into the ‘I need to review it more’ pile. So basically, you always have two piles with the items moving back and forth.

An I know it pile which you review once a day.

An I need to review it more pile which you review at least three times a day.

You keep this up everyday until all the items are in the I know it pile.

If you want to retain the information truly long-term, you’ll need to review the entire pile at least once a week for several months, and then at least once a month for several years.

Special note: If you use the information you have placed in your memory in your daily life (i.e. names, phone numbers, addresses, multiplication tables) then the information will stick in your memory and you won’t have to review it on any timetable. However, if your don’t use the information, or at least review it occasionally, you will tend to forget just about anything.

Our brains are not really designed to recall everything we have ever learned or done. We have selective recall and tend to remember what we use, so if you need to remember a skill or information, use it, or at least review it!

And now back to my student…

“Since you did not use ‘the card thing,’ you’re gonna have to use association to remember,” I suggested. “Try to associate each of the terms with words or ideas that you already know. Right now, you can’t remember what Cognitive bias refers to. So look at the word cognitive. Dose it remind you of any other words?”

Her nose wrinkled up as she answered, “Recognition?”

“Good, both have the root word gno, which is Latin for to know. So both words have to do with how we know things. When we recognize something that we have seen before, we essentially re-know it. Now, cognitive is how we know things—how we process and access information as it come in—and in this case, we know things through our biases. So that being said, what does cognitive bias mean?”

“It means that we interpret things through our biases,” she answered slowly.

“And halleluiah, cause that’s pretty much the right answer. Cognitive bias refers to our the tendency to act in less than rational ways due to our limited ability to process information objectively. It’s an umbrella term for all the other biases that you’re trying to remember for your test. Now, a confirmation bias is one such bias. It simply states that we tend to more easily process and accept information that we already agree with, while we tend to ignore and disregard information that contradicts what we accept as true and real.”

"Right,” she closed her eyes as she strained to remember. “Cognitive is the umbrella term; confirmation is the stuff that confirms.”

“Good, so now, what is ingroup bias versus outgroup bias?”

“Oh, I know this one,” she clapped her hands. “Ingroup is where we tend to favor people that we consider in our own group. Outgroup is where we tend to dislike people that we don’t consider part of our group. And I have the perfect example for the test.”

“I’m listening.”

“A Trump for President t-shirt.” She paused to see how I was taking her example before continuing, “Get it? If you supported Trump, you would instantly feel an affinity for that person. If you hated Trump, you would instantly feel dislike for the person.”

“You’re right,” I snickered. “That is a perfect example, and most timely.”

She cocked her head to one side, suddenly thoughtful. “You know, I think that’s why I like that example so much. It really shows how subconscious our biases are. It’s like we feel the affinity or the dislike so quickly, and it happens so automatically that we don’t really have any choice in the matter.”

“I think people often mistake their biases for what they call gut reaction, or intuition,” I agreed. “Now, back to your test review. Can you think of an example where a bias might be a good thing; something to listened to?”

“Aren’t all biases kind of bad?”

“Not necessarily. I have an extremely heathy bias against playing with black widows spiders, or putting my hand on a hot stove. I also have a pretty strong bias against jumping off cliffs into deep water.”

“Where’d that come from?”

“Personal experience,” I laughed. “You know that famous cliff diving rock at Waimea Bay?”

“Yeah.”

“When I was in high school, I got talked into jumping from it.” My head shook violently at the memory. “Never again.”

“What was wrong about that? Sounds like fun.” Was she laughing at my discomfort?

“Fun for some,” I scowled. “However, I discovered how much I really hate falling. I distinctly remember, while I was falling, I was able to think, ‘I’m falling…I’m still falling…Geeze, I’m still falling.’ It was about the time that I realized how much I hated falling that I hit the water.”

She laughed harder, “Would that be an example of hindsight bias?”

“How so?”

“Well,” she tried to explain. “You’re predicting a future experience based on a past experience. Your hindsight is telling you that you would hate falling just as much if you tried it again.”

“Not quite,” I shook my head. “Hindsight bias has more to do with people feeling the need to say, ‘I told you so,’ or ‘I knew it would happen.’ Hindsight bias is something people tend to use to make themselves feel better when something has gone terribly wrong. Like a bad break up when people say, ‘I knew he was bad news all along.’ Or when the stock market crashed and all the experts were suddenly saying, ‘All the signs were there.” I stretched in my chair, adding, “No, my aversion to high diving is more like an expectation bias, because I’m basing my decision to never high dive again on what I expect will happen. Expectation bias is also kind of why I stopped acting.”

“A cognitive bias tanked your acting career?”

“Yeah, well, sort of. When I lived and worked in Portland, I went to auditions all the time, no problem. I got cast in nearly everything I went out for, so I didn’t mind auditions. It was a chance to see my friends. Then I decided to try my luck in Los Angeles. At first I did fine. In fact, I got two of the first jobs I went out for, but over time the auditions got to be such a drag. I began to feel ‘why am I bothering.’ Eventually I stopped auditioning entirely. My expectations of a bad ending colored my decision making, and as a result, I became a full time teacher.”

“That’s kind of sad.”

“Hum,” I shrugged. “It is what it is. I suppose the important thing to remember is that our biases color our decisions and outlooks all the time. It becomes our responsibility to be aware of them, so we can use them as the survival instincts they’re intended to be, but overcome them when they’re likely to steer us wrong.””

“That sounds a lot easier than it is,” she complained. “I mean, how can you manage something that happens so instantaneously that you aren’t even aware of it?”

“I suppose that’s where guidepost eight comes in.”

“What does the Power of Responsibility have to to do with cognitive biases?”

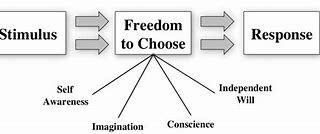

“Not much, unless you use it the way Viktor Frankel coined it. Response-ability, or the ability to choose ones response in any given circumstance.”

“He’s the guy who said that the last human freedom is our freedom to choose our attitudes, right?”

“I take it from your comment that you have still not read his autobiography even though I’ve recommended it several times.”

She groaned. “Life’s depressing enough. I don’t need to be reading about some guy’s life as a prisoner in Auschwitz.”

“It’s not about ‘some guy’s’ life in Auschwitz,” I countered. “It’s about prisoner 119,104; a man who through luck and determination survived Auschwitz. More importantly, it’s about what he, a trained psychologist, learned about human nature while in Auschwitz. You say that you’re thinking about going into psychiatry. I’m thinking that you might find his autobiography interesting.”

“No,” she shook her head. “You just don’t like it when people quote from stuff they haven’t read themselves.”

“I do like to read quotes in their context. Consider Frankel’s most famous quote. It’s one you see all the time on the internet. ‘The last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.’ The meaning changes a bit when you read it within it’s context, look…” and I pulled up the PDF copy of his book on my phone:

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

“And there were always choices to make. Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity to become molded into the form of the typical inmate.”

Source: (Viktor Frankel, Man’s Search for Meaning, p. 86-7), Free PDF Download, or read free online.

I continued my lecture when she looked up, “After the war, Frankl went on to found a form of existential therapy called logotherapy, which advances the idea that the primary motivational force of individuals is to find meaning in life.”

“I still don’t see what any of this has to do with biases, or response-ability.”

“His fundamental insight was that between stimulus and response, we have the freedom to choose our response. We don’t have to be a victim of our fears, our emotions, our circumstances, or even our biases. We can use our self-awareness, our imagination, our conscience, and our independent will to choose our best response in any given circumstance.”

“We can always choose our attitude,” she murmured to herself.

“We have the response-ability to choose our attitude,” I corrected.

“So,” she looked at me oddly. "You allowed your biases to change your attitude about auditioning, and so you stopped auditioning.”

“Thereby guarantying the end of my acting career, yes.” I suddenly felt a little wistful. “And I’ll never know how my life would have evolved had I chosen to not listen to those biases.”

“Expectation bias messes up a lot of people doesn’t it? I mean, I can think of a dozen things that I don’t do because I expect them to go wrong. People I don’t confront because I am afraid of how they’ll react. Stuff like that.”

“There are a number of what I would call ‘negative behavioral types’ who count on that very bias to get away with stuff.”

“Like who?”

“Ever known anyone who gets angry whenever people disagree with them, or anyone who just keeps on arguing until they get their way?”

“Yeah,” she hesitated.

“People like that have developed their behavior because it works for them. Others give in to them without argument because their expectation bias tell them that arguing would be pointless, or ugly. Result, the ‘behavioral type’ gets their way.”

“Man, I just had a flash about this guy I know. He does that very thing. I think he also has that bias where people assume that other people are always talking bad about him.”

“Are you referring to hostile attribution bias, where people tend to interpret the ambiguous behavior of others as hostile?”

“Yeah, cause every time he does start to get angry over a disagreement, he starts screaming about how everyone is out to get him, or accusing people of treating him badly, even though what they did had nothing to do with him.”

“Must make for a lovely dinner date,” I grimaced.

She was suddenly thoughtful. “I suppose, because it is a bias, he doesn’t even realize how messed up his reactions are. You know, because the bias makes his reaction partly subconscious.”

“You’re very likely right,” I started to pack up.

“So how would you handle a guy like that?”

“I think you mean how should I handle someone like him, not how would I handle someone like him. Because of my own bias against arguing, I tend to do everything wrong. I curl up in a small ball and hide until its over, then pretend it never happened. Not very effective.”

She laughed, “Okay, so how should you handle someone like him?”

“You should think of his tirade as a good time to practice setting boundaries. First, you stand up, so you are in a position of power. Second you stay calm and don’t react. Don’t take anything they’re yelling personally. Above all, you do not try to get a word in. You simply take a deep breath to center yourself, and remind yourself that between stimulus and response, you have the freedom to choose your response. Finally, you calmly set the boundary, attempting to use ‘I’ statements instead of ‘you’ statements. ‘You’ statements will be turned against you.”

“‘You’ statements?”

“Statements that tell them what they need to do. ‘You need to calm down,’ or '‘Don’t yell at me,’ would be two examples of a ‘You Statement.’ A better way of putting it might be, ‘I will speak to you about this when the yelling stops.’ Then you calmly go about your business until the yelling stops.”

“That’s probably gonna get them more angry.”

“That’s their problem, not yours. Once the yelling subsides, you can attempt to discuss the issue rationally.”

“And if they won’t?”

“I suppose that’s when you decide how important the relationship is.”

“Hum,” she sat considering, while I continued stacking up the notes she had strewn across my table. Giving the pile a final pat, I slid them across to her. “But,” she protested. “I haven’t memorized all the biases yet.”

“I have another student coming, so you’re gonna have to finish on your own. I recommend that when you get home, you write down all the ones you remember, along with your examples, then go to your notes and make cards for the ones you didn’t remember. You can study those cards from now until tomorrows test.”

“A short cut for ‘the card thing?’” she quipped snidely, reaching for the pile.

“You could call it that.” She looked down at the pile of notes in her hand as if they were a firing squad, so I added. “I’m sorry, but I can’t take the test for you, and I have another obligation.”

She sighed and began shoving things around in her backpack to make room. “This is silly,” she said suddenly and froze with her eyes closed. I watched as she slowly took a breath in through her nose and then out through her mouth. She did this three times, then said to herself, “I will not let my expectations about this test spoil my mood or actions. I will take Miss Lynn’s advice for studying the rest of the material, and I will prepare to the best of my ability for tomorrow.” With that, she shoved the rest of her belongings into her backpack, stood up with a salute to me, and headed towards the door.

“I have faith in you,” I called after her.

“Yeah right,” she called back as she shut the door.

For those of you who would like another look at our notes on Cognitive Biases, I’ve attached a link below.

Until next time…have a worthwhile ride.