Navigating a Whackadoodle World: Episode 61A, or Your Cheat Sheet of Cognitive Biases

A Whackadoodle resource for those wanting to learn more about the many Cognitive Biases that wire our mind to misjudge things, here is a list with examples of the 37 most common of the biases.

I have assembles a list of the 37 most common Biases that we encounter in our daily lives. My main resource for this list has been the ultimate cheat sheet website, scribbr.com. If you want to learn even more about Cognitive Biases, I invite you to visit their website. For those of you who are happy with a cheat sheet derived from a cheat sheet, I invite you to read the following:

A special note before you start reading: Remember to not fall victim to Primacy Bias, which before you ask, is our tendency to more easily recall information that we encounter first in any presentation, while forgetting information that comes later. In other words, if you try to remember all the biases in one sitting, you will remember only the first few. So instead of trying to take them all in at one, I suggest that you focus on one or two a day. That way, you will be able recall them individually and look for how each influences your interactions each day. Try to come up with your own examples for the few you choose to focus on each day. Creating your own examples is an excellent memory aid in any situation.

Cognitive biases

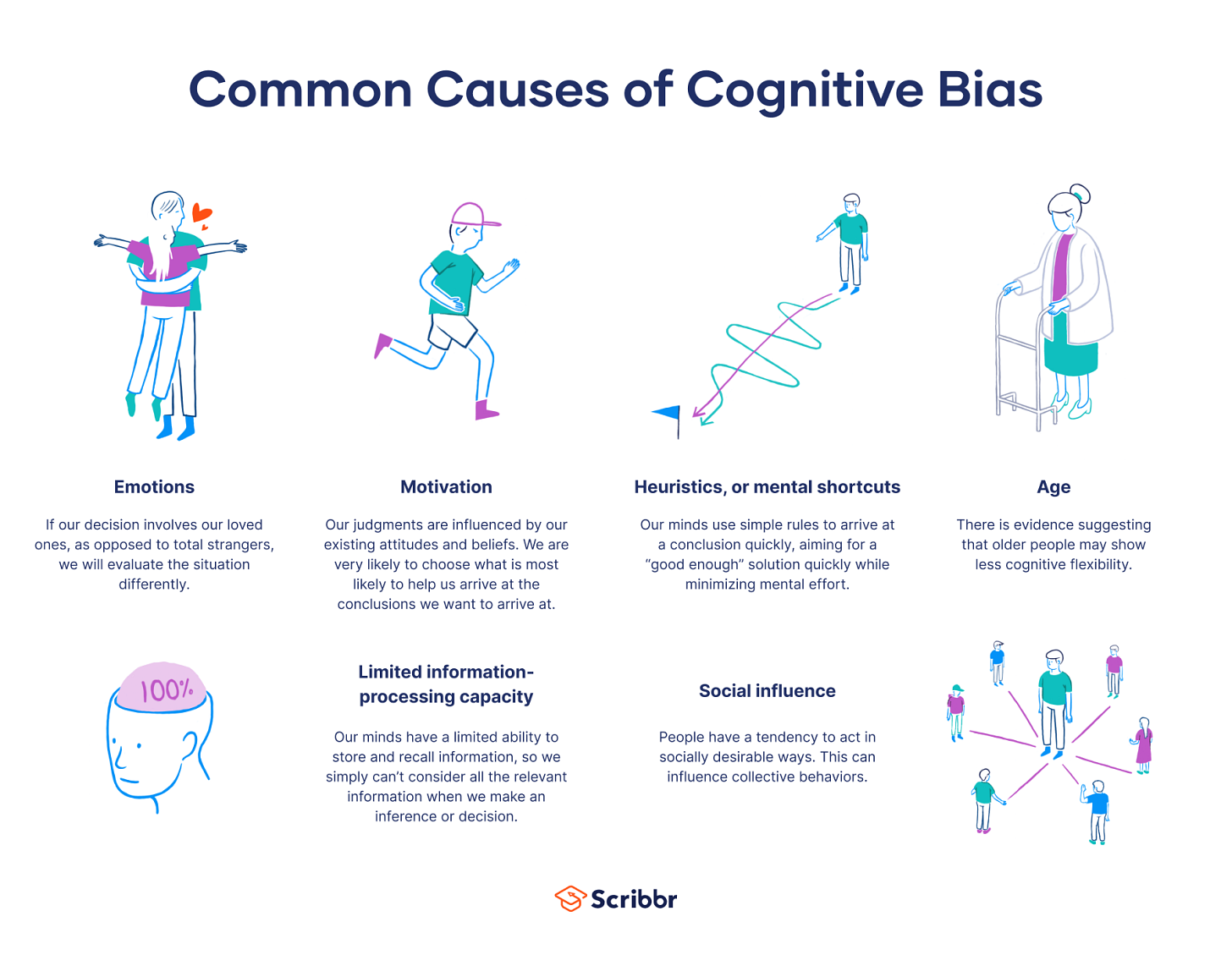

Cognitive biases are the tendency to act in an irrational way due to our limited ability to process information objectively. Cognitive Biases are not always negative, but they can cloud our judgment and affect how clearly we perceive situations, people, or potential risks.

Example: One common manifestation of cognitive bias is the stereotype that women are less competent or less committed to their jobs. These stereotypes may linger in managers’ subconscious, influencing their hiring and promoting decisions. This, in turn, can lead to workplace discrimination.

Below are examples of common Cognitive Biases

Actor-observer bias is the tendency to attribute the behavior of others to internal causes, while attributing our own behavior to external causes. In other words, actors explain their own behavior differently than how an observer would explain the same behavior.

Example: As you are walking down the street, you trip and fall. You immediately blame the slippery pavement, an external cause. However, if you saw a random stranger trip and fall, you would probably attribute this to an internal factor, such as clumsiness or inattentiveness.

Anchoring bias describes people’s tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive on a topic. Regardless of the accuracy of that information, people use it as a reference point, or anchor, to make subsequent judgments. Because of this, anchoring bias can lead to poor decisions in various contexts, such as salary negotiations, medical diagnoses, and purchases.

Example: You are considering buying a used car, and you visit a car dealership. The dealer walks you around, showing you all the higher-priced cars, and you start worrying that you can’t afford a car after all. Next, the car dealer walks you toward the back of the lot, where you see more affordable cars. Having seen all the expensive options, you think these cars seem like a good bargain. In reality, all the cars are overpriced. By showing you all the expensive cars first, the dealer has set an anchor, influencing your perception of the value of a used car.

The affect heuristic occurs when our current emotional state or mood influences our decisions. Instead of evaluating the situation objectively, we rely on our “gut feelings” and respond according to how we feel. As a result, the affect heuristic can lead to suboptimal decision-making.

Example: You have been applying for jobs for the past few months. Your last application successfully landed you an interview at a big tech company, but you didn’t make it to the second round of interviews. You were very excited about the opportunity, and now you feel disheartened. A friend forwards you another job posting for a similar position at a smaller company. You decide not to apply, even though you are qualified. Because of your state of mind, you feel that there is a good chance that you won’t get that job either.

The availability heuristic occurs when we judge the likelihood of an event based on how easily we can recall similar events. If we can vividly remember instances of that event, we deem it to be more common than it actually is.

Example: When asked if falling airplane parts or shark attacks are a more likely cause of death in the United States, most people would say shark attacks. In reality, the chances of dying from falling airplane parts are 30 times greater than the chances of being killed by a shark. People overestimate the risk of shark attacks because there are far more news stories and movies about them. As a result, images of shark attacks are easier to bring to mind. If you can quickly think of multiple examples of something happening, then you are tricked into thinking it must happen often.

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon refers to the false impression that something happens more frequently than it actually does. This often occurs when we learn something new. Suddenly, this new thing seems to appear more frequently, when in reality it’s only our awareness of it that has increased.

Example: Suppose that you decide to buy a car, and you have set your mind on a specific blue model. In the next few days, you see that blue color wherever you go. It feels like suddenly, everyone is driving a car in that color.

Belief bias refers to the tendency to evaluate the strength of an argument based on its plausibility. Instead of considering the validity of the argument itself, we rely on our prior knowledge and beliefs. In other words, if an argument aligns with our beliefs, we tend to accept it.

Example: You come across the following statement:

“Scientific studies have consistently shown that there is little nutritional difference between organic and conventional foods.”

Because you firmly believe that an all-organic diet is superior to a conventional one, you are skeptical and quickly dismiss the argument, even though it provides scientific evidence.

Bias for action (also called action bias) is the tendency to favor action over inaction. Because of bias for action, we often feel compelled to act, even when we don’t have all the information we need or are uncertain about the outcome.

Example: Suppose that you are a sales representative and your team is under pressure to meet the monthly sales quota. Here are two possible scenarios:

When you realize that you are not on track to meet your goals, you feel frustrated. However, since you are not the head of the department, there’s nothing you can do. You wait for instructions, hoping that your supervisor will figure something out.

When you realize that you are not on track to meet your goals, you immediately take on more responsibility and start cold-calling. Because of your quick response, your team meets its goals for the month.

In the second scenario, you clearly showed bias for action.

The egocentric bias refers to people’s tendency to fixate on their own perspective when examining events or beliefs. Under the egocentric bias, we see things as being more centered on ourselves than is actually the case. This results in a distorted view of reality that makes it difficult for us to acknowledge other people’s perspectives and feelings.

Example: You are asked to give a welcome speech to new students. As you start talking, you notice how nervous you feel, and you assume that your nervousness is obvious to others because of your movements or your shaky voice. This thought increases your stress even more. However, in reality none of this is obvious to your audience. In fact, they are more stressed out because this is their first day of school. The egocentric bias causes you to focus on your own anxieties and fail to see things from the other person’s point of view.

The framing effect occurs when people react differently to something depending on whether it is presented as positive or negative. In other words, our decision is influenced by how the information is presented rather than what is being said.

Example: While doing your groceries, you see two different beef products. Both cost and weigh exactly the same. One is labeled “80% lean” and the other “20% fat.” Comparing the two, you feel that 20% fat sounds like an unhealthy option, so you choose the 80% lean option. In reality, there is no difference between the two products, but one sounds more appealing than the other due to the framing effect.

The halo effect occurs when our overall positive impression of a person, product, or brand is based on a single characteristic. If our first impression is positive, the subsequent judgments we make will be colored by this first impression.

Example: The halo effect is a common bias in performance appraisals. Supervisors often evaluate the overall performance of an employee on the basis of a single prominent characteristic. If an employee shows enthusiasm, this may influence the supervisor’s judgment, even if the employee lacks knowledge or competence in some areas. This may lead the supervisor to give them a higher rating due to their enthusiasm. Because of the halo effect, one positive characteristic may overshadow all other aspects of the employee’s performance.

Hindsight bias is the tendency to perceive past events as more predictable than they actually were. Due to this, people think their judgment is better than it is. This can lead them to take unnecessary risks or judge others too harshly.

Football fans often criticize or question the actions of players or coaches in what is known as “Monday morning quarterbacking.” They often claim they knew the result before the game was over and that the outcome was easily preventable. This is particularly the case after a loss. However, it is easy to pass judgment from a position of hindsight and to recognize bad decisions after the fact. When you know the result, you know what worked and what didn’t work during the game. Hindsight bias is the reason behind the “Monday morning quarterback” phenomenon.

Hostile attribution bias is the tendency to interpret the ambiguous behavior of others as hostile. Under hostile attribution bias, people assume that others have negative intentions towards them and want to hurt them, even when others have no such intentions.

Example: You notice two people sitting across your table at a coffee shop, whispering and laughing. Because they occasionally look your way, you assume they must be laughing about you. However, that’s not the case—they simply look at you because you happen to be sitting right across them.

Ingroup bias is the tendency to favor one’s own group over other groups. Ingroup bias affects our perception of (and behavior towards) others, giving preferential treatment to the members of our own group while excluding other groups.

Example: You are stuck in traffic, trying to change lanes and exit the highway. A car approaches and tries to cut you off. You are annoyed until you notice the other car has a bumper sticker of your favorite sports team. You give them a friendly nod and let them pass.

Normalcy bias is the tendency to underestimate the likelihood or impact of a negative event. Normalcy bias prevents us from understanding the possibility or the seriousness of a crisis or a natural disaster.

Example: Officials issue a hurricane warning in your area, advising everyone to evacuate their homes. On your way out, you run into your neighbor, who has no intention of leaving because they believe it is “just another storm.” Their conviction that it’s not going to be that bad and their refusal to heed the warnings are signs of normalcy bias.

Outgroup bias is the tendency to dislike members of groups that we don’t identify with. We not only have negative feelings and ideas about people who are not part of our group, but we also tend to exhibit hostility towards them. This happens even if we know nothing about them as individuals.

Example: As part of a student exchange program, a group of foreign students arrive at your university. Because they are a little hesitant to speak English, you notice that most of your fellow students are not making an effort to get to know them better. At the cafeteria, you overhear some of your classmates talking about the visiting students, agreeing that “people from that country are all unfriendly.”

Overconfidence bias is the tendency to overestimate our knowledge and abilities in a certain area. As people often possess incorrect ideas about their performance, behavior, or characteristics, their estimations of risk and success often deviate from reality.

Example: College students often overestimate how quickly they can finish writing a paper and are forced to pull an all-nighter when they realize it takes longer than expected. This is overconfidence bias at play.

Perception bias is the tendency to perceive ourselves and our environment in a subjective way. Although we like to think our judgment is impartial, we are, in fact, unconsciously influenced by our assumptions and expectations.

Example: After a few weeks at your new job, you notice that some of your colleagues always go for after-work drinks on Fridays. It’s not an official team event, but each week the same person asks who’s joining and books a table. However, no one ever asks the older colleagues to join, assuming that they won’t be interested.

Negativity bias is the tendency to pay more attention to negative information than to positive information. Here, more weight is given to negative experiences over neutral or positive experiences. Due to negativity bias, we are much more influenced by negative events or information than by positive counterparts of equal significance.

Example: You are hiking with friends. While enjoying the scenery, you suddenly see a rattlesnake. The snake immediately slithers away. However, when asked about the hike later, you remember the snake incident more vividly than the beautiful scenery.

Optimism bias is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive events and underestimate the likelihood of negative events. Optimism bias causes most people to expect that things will work out well, even if rationality suggests that problems are inevitable in life.

Example: You’ve just bought a new bike, and the salesperson asks you whether you also want to look for a helmet. Because you’ve been riding a bike since you were young, you think the chances of getting involved in an accident are really small. You conclude that you’ll be fine without it. Optimism bias makes you underestimate the risk of riding a bike without a helmet.

Primacy bias is the tendency to more easily recall information that we encounter first. In other words, if we read a long list of items, we are more likely to remember the first few items than the items in the middle.

Example: You are attending a lecture at school. At the beginning, you feel like you can absorb all the information and follow the topic. After a while, your mind starts to wander and only when the lecture is drawing to an end do you tune in again. Later that day, as you try to explain to a friend what the lecture was about, you realize that you can vividly recall the first part of the lecture but not the middle.

Recency bias is the tendency to overemphasize the importance of recent experiences or the latest information we possess when estimating future events. Recency bias often misleads us to believe that recent events can give us an indication of how the future will unfold.

Recency bias can be observed in sports betting, as it leads to an over-dependence on recent outcomes. Bettors will follow a team on a winning streak or avoid a team on a losing streak, even though recent successes or failures don’t provide any insight into how things will play out in the future.

The representativeness heuristic occurs when we estimate the probability of an event based on how similar it is to a known situation. In other words, we compare it to a situation, prototype, or stereotype we already have in mind.

Example: You are sitting at a coffee shop and you notice a person in eccentric clothes reading a poetry book. If you had to guess whether that person is an accountant or a poet, most likely you would think that they are a poet. In reality, there are more accountants in the population than poets, which means that such a person is more likely to be an accountant.

Self-serving bias is the tendency to attribute our successes to internal, personal factors, and our failures to external, situational factors. In other words, we like to take credit for our triumphs, but we are more likely to blame others or circumstances for our shortcomings.

Example: Α student who performs well on an exam may ascribe their success to their excellent preparation and intelligence. In the case of a poor performance, the same student would likely think that the exam was too difficult or that the questions did not correspond to the material taught.

Status quo bias refers to people’s preference for keeping things the way they currently are. Under status quo bias, people perceive change as a risk or a loss. Because of this, they try to maintain the current situation. This can impact the quality of their decisions.

You are having dinner with your friends at a restaurant you go to often. Looking at the menu, you feel tempted to try a new dish. However, you are really hungry, and you don’t want to risk choosing something you don’t like.

Because of status quo bias, you want to be on the safe side. You order the same dish as you always do, rather than take the risk on a new (and potentially tastier) option.

An ecological fallacy is a logical error that occurs when the characteristics of a group are attributed to an individual. In other words, ecological fallacies assume what is true for a population is true for the individual members of that population.

Example: You are reading a news story about the wealthiest states in the country. Assuming that wealthier states contain more wealthy people is an ecological fallacy. Indeed, it could be due to the fact that they contain a small number of extremely rich individuals.

Other Types of Biases

Affinity bias is the tendency to favor people who share similar interests, backgrounds, and experiences with us. Because of affinity bias, we tend to feel more comfortable around people who are like us. We also tend to unconsciously reject those who act or look different to us.

Example: Your company has hired several new people. During a team meeting, all the new colleagues take turns introducing themselves. One of them is your age, and it turns out that you both studied product design and have worked at similar companies. You instantly feel that this particular person is a good fit for the team.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and prefer information that supports our preexisting beliefs. As a result, we tend to ignore any information that contradicts those beliefs.

Confirmation bias is often unintentional but can still lead to poor decision-making in (psychology) research and in legal or real-life contexts.

Example: During presidential elections, people tend to seek information that paints the candidate they support in a positive light, while dismissing any information that paints them in a negative light. This type of bias is more likely to occur while processing information related to emotionally charged topics, values, or deeply held beliefs.

Conformity bias is the tendency to change one’s beliefs or behavior to fit in with others. Instead of using their own judgment, individuals often take cues from the group they are with, belong to, or seek to belong to about what is right or appropriate. They then adapt their own behavior accordingly.

Example: Your friends are making plans for an upcoming concert that they are very excited about. Last time they went to a concert, they were talking about it for a week afterwards, and you felt left out because you did not go with them. Although you are not really keen on that kind of music, you decide to join them this time so as not to feel left out.

Correspondence bias is the tendency to form assumptions about a person’s character based on their behavior. When we try to explain why people act in a certain way, we often focus on personality traits, underestimating the power of specific situations to lead to specific behaviors. In other words, people are inclined to think that others’ actions reflect their personality.

Example: You are driving in heavy rain, and you notice another driver in your rearview window speeding and overtaking other cars. Because of correspondence bias, you are more likely to assume that they are a reckless driver, when perhaps it’s the case that they are rushing to the hospital.

Explicit bias is a demonstration of conscious preference or aversion towards a person or group. With explicit bias, we are aware of the attitudes and beliefs we have towards others. These beliefs can be either positive or negative and can cause us to treat others unfairly.

Example: Your teacher has graded your math exams and is handing back your results. As they walk by a blonde student, the teacher makes an offhand remark expressing shock at her high score because “blondes are dumb.”

The Hawthorne effect refers to people’s tendency to behave differently when they become aware that they are being observed.

Example: Students might be shocked to learn that their favorite teacher smokes, drinks, and swears because their teacher behaves differently while being observed by his/her students.

Implicit bias is a collection of associations and reactions that emerge automatically upon encountering an individual or group. We associate negative or positive stereotypes with certain groups and let these influence how we treat them rather than remaining neutral.

Example: You are walking on a street at night and notice a figure wearing a hoodie coming your way. You immediately sense danger and try to cross the street. The other person pulls an object out of their pocket, and you start running because you think it’s a weapon. Looking back, you realize your mistake: the person was simply answering their phone.

The placebo effect is a phenomenon where people report real improvement after taking a fake or nonexistent treatment, called a placebo. Because the placebo can’t actually cure any condition, any beneficial effects reported are due to a person’s belief or expectation that their condition is being treated.

Example: You participate in a double-blind clinical trial on a new migraine medication. For the next month, each time you experience a migraine, you are instructed to take a pill and rate the pain intensity. You feel that the pill relieves the symptoms, but at the end of the month you find out that you were given a placebo—and not the new medication. The perceived improvement you experienced was due to the placebo effect.

Publication bias refers to the selective publication of research studies based on their results. Here, studies with positive findings are more likely to be published than studies with negative findings. Positive findings are also likely to be published quicker than negative ones. As a consequence, bias is introduced: results from published studies differ systematically from results of unpublished studies.

Example: In 2014, Franco et al. studied publication bias in the social sciences by analyzing a sample of 221 studies whose publication status was known. The sample was drawn from an archive called Time-sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences (TESS). The authors found that only 10 out of 48 null results were published, while 56 out of 91 studies with strongly statistically significant results made it into an academic journal. In other words, there was a strong relationship between the results of a study and whether it was published, a pattern that indicates publication bias.

The Pygmalion effect refers to situations where high expectations lead to improved performance and low expectations lead to worsened performance. Although the Pygmalion effect was originally observed in the classroom, it also has been applied to in the fields of management, business, and sports psychology.

Example: You want to research the influence of two storytelling methods on the vocabulary size improvement of children. To test this, the children are either given 20 minutes of storytelling from their teacher or 20 minutes of computerized storytelling. You strongly believe the human aspect is needed to aid in the vocabulary development of children. You encourage the children in that group to pay attention and be excited, whereas you don’t show this behavior to the computer group. The children in the first group are now paying more attention and feeling better about themselves than children in the other group, potentially leading to a Pygmalion effect.

A self-fulfilling prophecy is a belief about a future outcome that helps to bring about its own fulfillment. This happens because the unconscious expectations that we hold can influence our actions and ultimately cause the initial prediction to become true.

Example: You have a big presentation coming up, and you are convinced that it won’t go well because you are nervous. As you present, your voice becomes shaky, you stumble over your words, and you keep looking at your notes. However, you’re not surprised because you already believed that it would go terribly. This is a self-fulfilling prophecy at work: when we are convinced about a negative outcome, we do very little to prevent it from happening. Because of this, it becomes a reality.

Vividness bias is the tendency to focus on certain attributes of a decision or situation while overlooking other elements that are equally or more important.

Example: People often prioritize a prospective employer’s reputation, the prestige of a title, or a higher salary over other things that they may value more, such as work-from-home possibilities or a shorter commute to work. Prioritizing prestige over what we actually value most is a sign of vividness bias.