Navigating a Whackadoodle World: Episode 59, or What's up with emotional intelligence anyway?

A Whackadoodle lesson in which I help my student with her paper on emotional intelligence and lean quite a lot myself, along with a small reminder of Guidepost Two: The Power of Definition and Belief.

Our tutoring session had just begun, and she was already hunched over her notebook, pen thumping rhythmically against the table top as she spoke, “I figure that I need to start the paper by explaining what emotional intelligence is, so I thought I would use this quote to explain it.” Shoving her notes in front of me, she added, “It’s by the guys who first came up with the concept.” I looked down and read:

The term “emotional intelligence” was coined in 1990 by psychology professors Peter Salovey and John D. Mayer, who defined emotional intelligence as “the ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior.” They concluded that the primary components of emotional intelligence were perceiving emotions, reasoning with emotions, understanding emotions, and managing emotions.

“It’s a nice quote,” I acknowledged. “But is there any reason you can’t use your own words to define emotional intelligence. Do you have to use a quote?”

“They explain it much better than I could. Besides, they have more authority than I do. I’m just a student writing a paper about something they came up with,” she insisted.

“I’d still like to hear your definition. When people can explain concepts in their own words, it’s a sure sign that they understand that concept themselves and are not just quoting others.”

“Fine,” she sighed and huffed. “I guess that I would define emotional intelligence as a measure of how well people are able to understand and control their own emotions, as well as understand and deal with the emotions of others. People who have high emotional intelligence have developed a number of skills that make interacting with others easier. People with low emotional intelligence, not so much.”

“Good. And what are those skill?” I prompted.

“It sort of depends on which model you follow, but they all have to do with understanding how emotions impact situations and people,” she sorted through her notes, all the while mumbling to herself. “There’re actually several theories about it, and they all define emotional intelligence differently. Their tests even measure different stuff, see.” She’d found the list she was looking for and pushed it before me. “There’s the Dr. Salovey and Dr. Mayer model with it’s four components, and the Bar-On Emotional Quotient model with it’s fifteen components, the Goleman model with it’s five components, and there’s even a Howard Gardner model which talks about eight types of intelligences, two of which incorporate emotional intelligence.” She began counting them off on her fingers. “Verbal/linguistic, logical/mathematical, naturalistic, visual/spatial, musical/rhythmic, body/kinetic, interpersonal intelligence, and intrapersonal intelligence. I found some pretty good videos on each model, and I’ve got reams of notes…”

“Hang on, hang on,” I placed my hand on top of hers, blocking her notes from view. “Are you writing a paper, an article, a thesis, or a book?”

“Huh?”

“Well, it seems to me that explaining what emotional intelligence is and giving people a chance to test their emotional intelligence quotient, well that’s an article. Adding a few tips about how to improve ones emotional intelligence might make it a paper. But trying to explain, compare, and contrast all the different models for testing emotional intelligence in one sitting? No,” I shook my head. “That’s more like writing a thesis, or a book. Heck, it could be a series of books because I bet you could write a whole book about each of the different models.”

Her face crumpled, “You’re right. It’s too much for one paper. I just don’t know what to leave out.”

“How about you start by telling your readers what all the theories have in common,” I suggested.

“Well,” she spent some time sorting out her thoughts. “All of them put a major emphasis on being what they call self-aware—aware of your own emotions and how they might be influencing your actions or attitude. They claim that people with high self-awareness are more likely to reflect before taking action, while people with low self-awareness are more likely to react impulsively and get caught up in emotional turmoil.”

“Sounds a lot like what my father calls being mindful,” I offered. “Okay, so self-awareness is one. What are are some others?”

“All the theories say it’s important to read other people’s emotions accurately, so that you can take those emotions into consideration when deciding how to react. They talk a lot about reading non-verbal cues like tone and body language. It’s actually a lot like the stuff you recommend in the guideposts. Anyway, they claim that people who can read emotions and non-verbal cues accurately get into misunderstandings less often, and find it easier to get out of them when they do.”

“I assume that people who don’t read those things accurately get into more misunderstandings?’

“Yeah,” she nodded. “Plus they say that people who can’t read people accurately are more likely to miss opportunities. Although, I’m not sure why.”

“Maybe it’s because they’re so caught up in the misunderstanding that they can’t see anything else.”

“Maybe.”

She was silent for a while, so I prompted again, “So is that all the different theories have in common?”

“No,” she shook her head as if to shake loose a thought before continuing. “They also put a lot of stock in being to able to regulate and manage your own impulses and emotions. They claim the skill helps people recover faster from negative emotions, like bad moods, so they don’t get derailed by them, while people who can’t control or manage their emotions often get overwhelmed by them.”

“Alright, so that’s three components—self awareness, awareness of others, and emotional control. Any more?”

“Yeah, they all say that the more empathetic you are the better. Which kind of sucks because there’s a lot of debate over whether empathy is innate, or whether it can be taught.”

“What do you think? Can empathy be taught?”

“Well, it seems to me that if people make a practice of putting people and situations into their full context, like you suggest in guidepost fourteen, people can’t help but become more empathetic. I mean when you really understand where a person is coming from and how they became who they are, you’re much more likely to understand them and feel for them, right?”

“Seems right,” I agreed. “So that’s four. Do we have a fifth?”

“Well, there is this one that not all of them have in common, but I think it’s important.”

“And that is?”

“Having a sense of wellbeing, and an ability to motivate oneself.”

“That sounds like two things.”

“Well, evidently they’re linked somehow. People who have a sense of wellbeing tend to be more confident and optimistic in general, so they’re better at problem solving, and motivating themselves; while people who don’t have a sense of wellbeing get caught up in the negative and risk depression. Plus, they often lack confidence, so they avoid risk.

“Humm,” I considered. “I suppose I can see that. Any thing else?”

“Well, there’s this,” she said, pulling out her iPhone and doing a quick search. “I checked out a bunch of emotional intelligence tests on the Internet. They were all pretty much the same, except most were like, ‘Give us your e-mail so we can send you the results’, or ‘Let us improve your EI; sign up for our course.’ I wasn’t having any of that. But I did find two test that are pretty cool, and I want people to be able to take them. One has only ten multiple choice questions and it’s pretty straight forward. The other has fifty-two statements and you have to choose how accurately or inaccurately the each statement describes you. It’s a little bit longer, but I think it’s probably more informative. Here,” she added, and handed me her cell phone.

“What do you want me to do with this?” I asked surprised.

“I want you to take the tests,” she answered briskly. “I told you last week that I wanted to see how maladjusted you are.”

I looked at the screen she had pulled up for me. “Do you really think that this the best use of our session?” I felt obliged to ask.

“I do,” she replied stubbornly.

“Alright.” I have to admit that I was curious. I took both tests while she hovered over me, the simple test first. I scrolled down the page a bit and found the test embedded in the article, but ten multiple choice questions later, I was informed:

You Have High Emotional Intelligence

You're comfortable dealing with social or emotional conflicts, and have no problem expressing your feelings even in difficult or awkward situations. Your friends tend to lean on you for support when they're going through a tough time, as your emotional intelligence makes you skilled at guiding them through it.

Bemused, I took the same test again, but this time I answered as though I was a certain person I knew—an ex-coworker who had managed to ruffle so many feathers at work that she ended up “politely let go.” This time I was informed:

You Have Low Emotional Intelligence

You may have a difficult time interpreting and acting on emotions and tend to feel uncomfortable around the emotional displays of others. This can lead to some extreme avoidance behaviors or occasional lashing out on your part, and others may feel that you lack empathy.

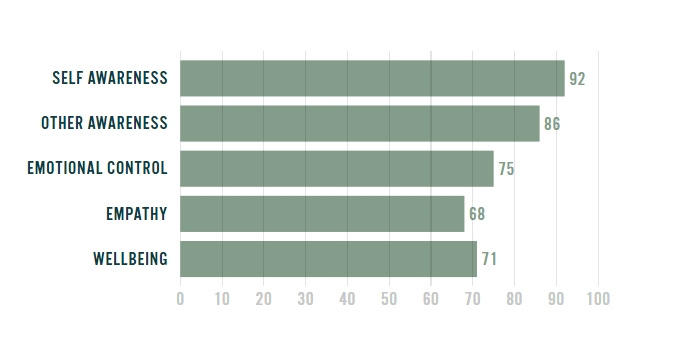

Laughing, I switched to the second test—the one with fifty-two statements in which I was to determine how accurately they described me. This time I was given a graph of how well I scored on each of the separate skills:

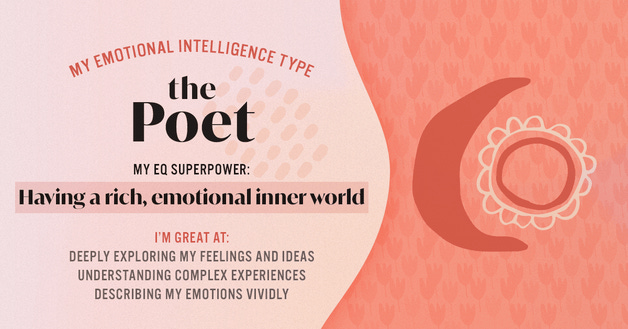

I was also was told that my Emotional Intelligence Type was that of the Poet, and provided a lovely result that I could share on social media.

“I few of my Facebook friends would love this,” I murmured to myself.

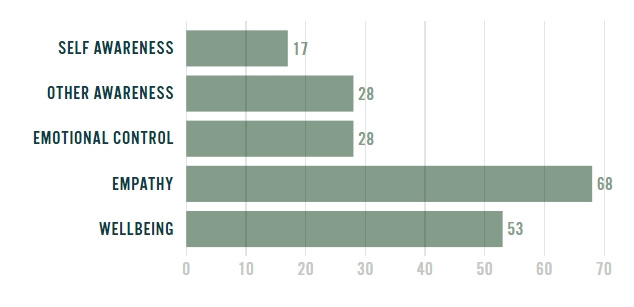

Feeling mischievous, I retook the test—once again pretending to be a certain someone. Again I was given a score for the separate skills, as well as a lovely image to share on social media. I have to admit that the results somewhat surprised me because I had never considered her very empathic; however, it all made sense when I looked at the graph and noticed that the only places where she’d scored above fifty were her sense of wellbeing and empathy. And when I really thought about it, I realized that she had been caring and sensitive—sometimes overly sensitive. She really had seemed happiest when she was helping others—even when her help got in other people’s way.

I was still considering the results when my student interrupted my thoughts with an impatient, “Well! What do you think?”

“I think that I might administer this test the next time I’m looking for a new roommate,” I said only half joking.

“Ha!” she slapped the table. “That’s the problem with the test. Companies are using it to screen out possible applicants just because the test says they might not have the skills to deal with other people effectively. That just seems wrong—weeding out people based on some unscientifically verified test. Plus, the whole self-assessment thing doesn’t really work on an unaware person, does it?”

“How do you mean?”

“Well, I personally know quite a few people who think they have great people skills, but the people around them might disagree. They’re just too polite to say anything.”

I laughed out loud, “You do have a point there.”

“And it is an important point,” she insisted. “Did you know that even so called experts question the validity and usefulness of those test? And the more I learn about them, the more I think they’re less about helping people, and more about emotional intelligence training becoming a multimillion dollar industry.”

“So why did you include the tests if they’re so controversial?”

“Because they’re kind of fun, and I figure that people should be able to see what they’re like and decide for themselves. I’m just not sure how to insert the controversy into my paper.”

“Why not put in a few words about it after your readers have had time to take the tests themselves?” I suggested.

“Yeah,” she looked uncertain. “But after the tests, I kind of wanted to go into some techniques that can help people improve their emotional intelligence. I mean, even if the tests are controversial, everyone seems to agree that the components they’re supposed to be measuring are valuable. So I thought I’d put in stuff like using an emotion wheel to become more aware of your emotions.” She reached into her notes again, and brought out a sample wheel. “See, it’s suppose to help people get comfortable naming their emotions while improving their emotional vocabulary.”

She pointed to the graphs center and went on to explain, “Most people are limited when they describe how they feel. They stick with seven possibilities—happy, bad, sad, disgusted, angry, surprised, and fearful—but the wheel is designed to get people to go deeper. It’s not just about being sad; it’s about feeling hurt, or lonely, or vulnerable. It helps people find words that more accurately describe their feelings, so they can be more aware of emotions in general. In fact, the Harvard Review has a really nice article on how to improve your emotional intelligence. Practicing the naming and recognizing of emotions is one of their main suggestions.”

I was barely listening. Her wheel had inspired a memory. “Reminds of a game I used to play with my students to improve their emotional vocabulary. I called it Sally seems. We would go around the room adding emotions to end the sentence. Sally seems sad. Sally seems unhappy. Sally seems downcast, or dejected, or despondent. If a player repeated an emotion, he or she had to start a new thread.”

“Ooh, I like that. Let me write it down.” She jotted something in her notes before adding, “I wonder if it would work as well playing the alphabet game using emotions. You know, list emotions following the ABCs. Angry is followed by Blissful, is followed by Crazed, is followed by Daring and so on.”

“What would you use for Q?”

“Humm,” she thought hard. “How about Quarrelsome?”

“Impressive.”

She smiled slightly at my praise then look down at her notes. “I found a whole bunch of websites full of ideas to improve a person’s emotional intelligence. I didn’t see much that I haven’t already learned from your books, but there were a couple more suggestions in that Harvard Review article that kind of surprised me. I thought I might finish with them.”

“And they are?”

“First, that you should actively seek out and ask for feedback regarding your personal interactions. Maybe even roll play difficult situations before they happen. Ask people how well they think you handled the situation, or how adaptable or empathetic you are, or how well you handle conflict. They said that while it may not always be what you want to hear, but it will often be what you need to hear, and will always help you to better understand the difference between how others see you and you see yourself.”

I had a sudden thought. “It would also be good practice for staying adaptable, open minded and in control of one’s reactions if one kept getting feedback that one didn’t want to hear.” But I kept my thoughts to myself and merely prompted her to continue. “Sounds good, and what’s the other one?”

“This one really surprised me. They said you should read literature that contains complex characters and situations because reading stories from other people’s perspectives can help you gain insight into other people’s thoughts, motivations, and actions. It also promotes empathy and helps enhance social awareness.” She shrugged. “I suppose the same could be said for watching movies that have complex characters and situations.”

“I would think that connecting to any of the arts would help people get in touch with their emotions. I know that years performing in plays helped me.” She didn’t reply, so I looked around the cluttered table. “Well is that it? Do we agree that you have a good start on your paper?”

She thought for a good long while before responding, “Yeah, I think it will do for now. Of course we spent the whole time planning this paper, so we didn’t have time to talk about Guidepost Two at all,” she grumbled.

“Oh, I think just a little reminder that Guidepost Two asks us to pay attention to our definitions and beliefs, especially those pesky limiting ones, because our definitions and beliefs influence our actions and our actions influence our circumstance might be enough for now. Besides, in a weird way, this has been about Definition and Belief since it turns out that being able to define ones emotions effectively is a major component in developing healthy working relationships.”

“If you think that’s enough,” she seemed doubtful.

“Sure, we can even make the naming of emotions an exercise for the week. Have them go people watching and see if they can guess how people are feeling based upon body language alone.”

“I like that.” She was about to say more when a car horn went off three times outside—the last honk held longer for dramatic effect. “Oh crap!” She shoved her notes into her backpack, not bothering to sort them. Managing a short thanks and a shorter goodbye, she tore towards the door with a loud, “I’m coming.”

I stretched in my chair, feeling all playful, and cheeky, and joyous, and accomplished. “Take that you silly emotion wheel,” I chuckled to myself, then rose to attend my demanding clowder of cats.