A Whackadoodle Civics Lesson

In which my student and I discuss how the Pareto Principle, Prejudice and Power help explain a lot, including voting laws.

“I’ve been thinking of that Pareto Principle you talk about in your books,” she told me at the end of our lesson.

“Go ahead.”

“Well,” she continued with an unexpected question. “How many people are actually Republicans, and how many people are actually Democrats?”

“Shoot,” I thought to myself. “I am a disenchanted Democrat who has stopped opening their emails because I already know what they will say.”

Instead of voicing my inner thoughts, I suggested, “Let’s see if Bing’s AI can find you an answer.” Sure enough, Bing’s AI found us an answer:

On December 17, 2020, Gallup polling found that 31% of Americans identified as Democrats, 25% identified as Republicans, and 41% as Independent.

Source: Political party strength in U.S. states - Wikipedia

She stared at the answer a while, then said, “So the Pareto Principle works here as well.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, already suspecting her answer.

“A certain percent of people are active on one side, and another percent of people are active on the other side. It’s the majority in the middle who will decide the difference, but those people are mostly silent.”

“Perhaps they prefer dancing at their own party,” I suggested drily.

She look up at me, concerned. “So it’s just those few people causing all the problems?”

“What few people are you talking about?”

“The twenty percent who keep getting all the attention. The twenty percent who keep getting elected.”

“Welcome to living in a Republic.”

“You always comeback to ‘We live in a republic not a democracy.’” She thew up her hands. “I still don’t get the difference.”

I took a deep breath and tried again, “Our country began with thirteen British colonies who had just fought a war to gain their independence from British rule. Thirteen colonies, each with their own constitution and laws. I can understand why Delaware, a small colony with few voters, might want to place a few limits on New York, a much larger colony with more voters.” I let her take that in.

“Is that why each state gets two senators no matter how may voters they represent? Because each colony wanted equal representation no matter how big or small they were?”

“Now you’re getting it.”

“Doesn’t that also have something to do with the electoral college?” she asked uncertainly.

“It certainly does. The electoral college is nothing more than a group of citizens sent by each state to declare their state’s choice for president. Each state get a certain number of votes. One vote for each of their Representative Districts, which is based on census population and gerrymandering, and one vote for each of their Senatorial Districts.”

“So, every state, no matter how populated or not, gets two Senators?”

“And at least one representative,” I nodded. Yes.”

“So each state gets two extra votes, no matter how many people they represent?” she wanted to confirm.

“That’s why we call it a Republic. In a Republic, the rights you have might just depend upon your zip code.” I sighed. “However, in the last seventy years America has attempted to become a Democratic Republic. It has attempted to remove the electoral college from the Constitution, and replace it with the popular vote. It has attempted laws to keep money out of politics. It has attempted to put in gerrymandering laws. It even passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which our supreme court kindly gutted in 2013.”

“What do you mean gutted?”

“They declared that one section of the act was out of date, so it could no longer be enforced.”

“Which part?”

“Section 5,” I told her. “The part that said the federal government has the both the right and responsibility to insure that each citizen, in whichever state, has an equal access to vote. The part which said if some states use voting law to make it harder for some citizens to vote, the federal government can step in.”

“Huh?”

“Oh, maybe the Brennan Center for Justice can explain it better than I can.” I picked up my iPad again and found the following:

In Shelby County v. Holder, a 5–4 majority mothballed (declared obsolete) the law’s Section 5, which required states with a history of racial discrimination in voting to get certification in advance, or “pre-clearance,” that any election change they wanted to make would not be discriminatory. The Supreme Court did this by holding that the formula used to determine which states and localities had to follow the Section 5 protocols was out of date.

For nearly 50 years, Section 5 had assured that voting changes in several states — including Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia — were transparent, vetted, and fair to all voters regardless of race…

…Within 24 hours of the Shelby ruling, Texas announced that it would implement a strict photo-ID law. In the years since, Brennan Center has consistently found that states previously covered by the preclearance requirement have engaged in significant efforts to disenfranchise voters. Our 2018 report, to cite one example, concluded that previously covered states have increased the purging of voters after Shelby when the purge rates in non-Shelby states stayed the same.

Just this month, voters — including many voters of color — faced faulty voting machines, long lines, and extended wait times to cast their ballots in Georgia, one of the states previously subject to preclearance requirement. If Section 5 were still in effect, the state, which has closed hundreds of polling places since Shelby, would have been required to clear its voting changes before enacting them.

Source: 7 Years of Gutting Voting Rights | Brennan Center for Justice, June 25, 2020, Article by Myrna Pérez

“Wow,” she said, then added. “But what’s wrong with voter ID laws? Aren’t they just supposed to keep elections safe?”

“Sure they can do that, but they can also disenfranchise a great many of voters.”

“How do voter ID laws disenfranchise people?”

“Do you know how expensive and difficult getting an official ID can be for some people? You have to pay for a copy of your birth certificate. You have to pay for the ID itself. In some cases, you have to provide proof of name change. I got married and changed my name. I got divorced and changed my name. I changed my name because I didn’t like my name. You have to pay for all that paperwork. Oh, and you have to show proof of residence. So what about people who have lost their residence, and pick up their mail at a Post Office? Post Office boxes are not accepted as proof of residence. Besides that, there are many communities where people don’t have street addresses, just the local post office. And then there are people who are between residences, living in a car, or on someone’s couch. What about them? Don’t they have the right to vote if they want to?”

“Okay, okay, I get it. Voter ID’s make it harder for some people to vote.”

“And so does limiting polling places,” I stubbornly continued. “So in certain neighborhoods people have to wait in six-hour long lines, while in other neighborhoods people walk right in and out.”

“I get it,” she insisted to shut me up. “What I don’t get is why some people don’t want everybody to vote.”

“Oh, that goes a long way back in US history. Women weren’t allowed to vote until 1920. Our brains were considered too soft and our emotions too changeable. And did you know that President Lincoln was only assassinated after he proposed a federal laws providing limited voting rights for the newly freed slaves. People leave that motivation for murder out of the history books. The new President, Andrew Johnson, left all voting laws up to the individual states, and soon those states were passing laws know as the Black Codes, which pretty much made voting impossible for African Americans in those states until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And consider that Native American’s only received the right to vote with The Snyder Act of 1924.”

“That tells me the when stuff happened, but not the why.”

“What do you think the why might be?”

She thought about it for a while. “The woman thing seems obvious. It’s like you said, ‘Our brains were considered too soft and our emotions too changeable to be trusted with a vote.’ I suppose it was something like that with Native American’s. They were considered too savage and uneducated to be trusted with the vote. And I suppose that the people in the south couldn’t be very happy with having the people they once owned voting like equals.”

“Besides, at that time in the south, forty percent of the population was African American. Consider how much power that voting block would have had.”

A light bulb went off in her head, “And the percentage of women to men has always been something like 50/50, so women make up a pretty huge voting block.” She looked up, “What percentages of Americans are indigenous?”

We looked her question up on my iPad, and discovered that Native American’s made up about two percent of of the American population. “That’s not a very big voting block,” she murmured uncertainly.

“Well, The Snyder Act of 1924 wasn’t really about voting rights. The Act simply granted them full citizenship, with all the rights guaranteed to American citizens.”

“Including the right to voted,” she concluded for me. She kept nodding to herself. “And that’s been true for all new immigrants. Once they become citizens, they get the right to vote. Does that mean that a lot of these voting laws are less about race, and more about the people who have always been in power wanting to stay in power?”

“I can’t argue with that logic,” I smiled, then added. “There’s a sentiment I often hear from people who claim not to be racist. It goes something like, ‘I don’t hate black people, so long as they stay in their place.’”

“There place being, ‘Out of power?’”

“Seems like a valid conclusion.”

“So, now I get the why. But, the new laws don’t forbid people from voting. They just make voting harder for everyone, even their own voters.” She began chewing her lower lip. “I still don’t see how the new voting laws can keep people from voting if people are determined to vote.”

“I suppose it goes back to the Pareto Principle you brought up earlier.”

“How so?”

“Well, according to the Pareto Principle, there will always be twenty percent on one side of any issue that’s is willing to jump through any hoop in order to vote. There will also always be another twenty percent on the other side of any issue that’s willing to jump through any hoop in order to vote. But that still leaves sixty percent in the middle who might just decide that voting has gotten too difficult and just isn’t worth it.”

“So if I make voting harder, those people in the middle are less likely to vote? And if I make voting easier, they are more likely to vote?”

“That’s what the Pareto Principle suggests anyway.”

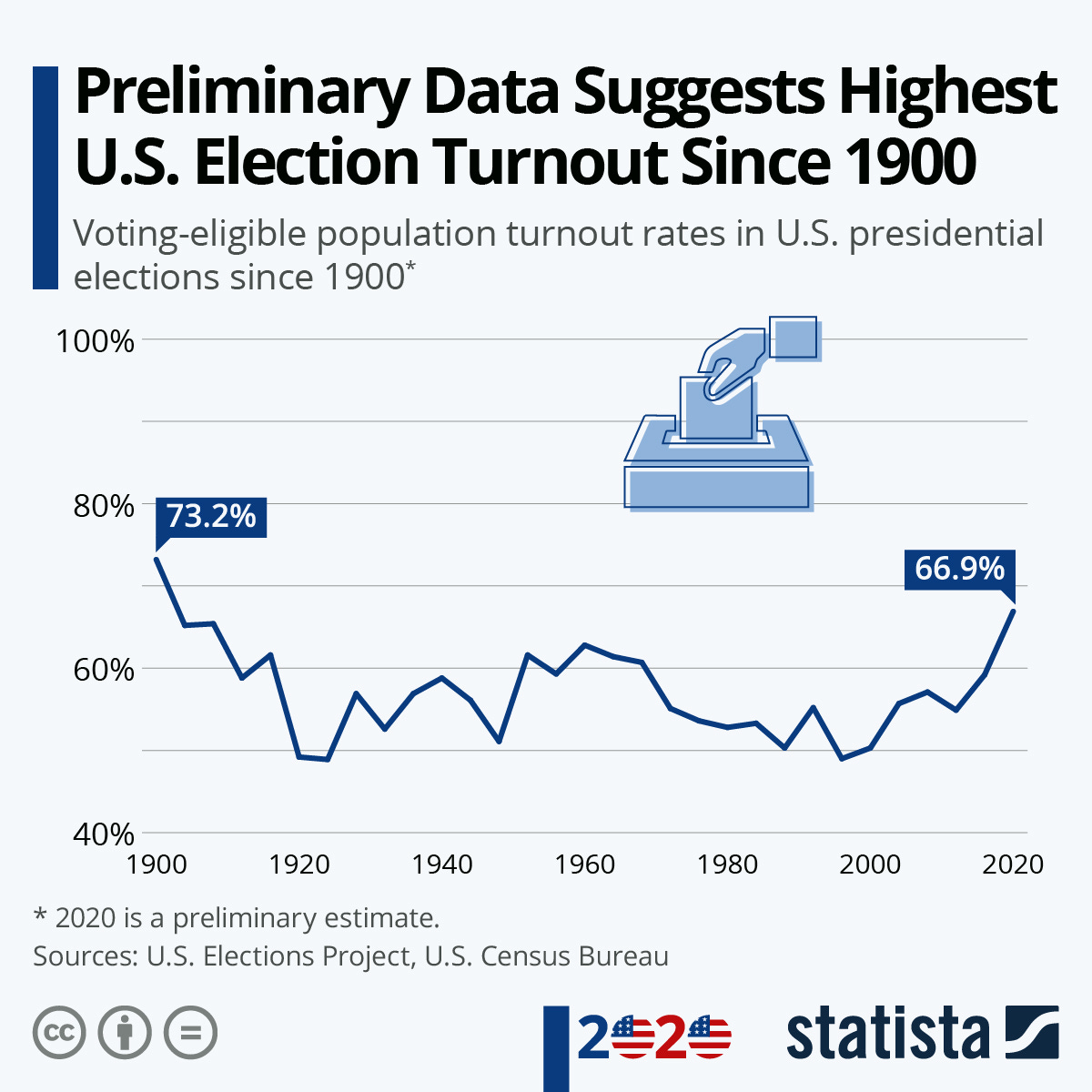

“How many Americans actually vote each year?”

We checked the iPad for an answer and found a cool chart on Statista:

“The percentage above the line,” she spoke at last. “That huge space represents the eligible voters from that year who didn’t even bother to vote?”

“Yep,” I confirmed.

She stared at the graph for some time and eventually concluded, “The Pareto Principle kind of sucks.”

I laughed. “Yeah, sometimes it does suck, but it’s a principle that shows up in the oddest places and tends to explain a lot.” I rubbed my hands together. “Now, are you ready for some homework?”

“What?” she pretended outrage. “You were hired to help me with my homework, not give me more.”

Ignoring her I went on, “I want you to download this chart, print it and then mark the years 1920 when women got the vote, 1924 when Native Americans got full citizenship, and 1964 when the Voting Rights Act was passed. You can mark any other important dates that have to do with voting laws as well. I want you to notice how the number of eligible voters who actually vote depends on who is eligible to vote and the voting laws at the time. Okay?”

“Okay,” she sighed and began filling her backpack. “But if I have any questions, you will regret it next time.”

“Leave any thoughts you have in the comment section, so you don’t have to wait for next week.”

I remember when I used to think everyone wanted everyone to vote.